Goldman's shared RE wisdom; RE Crisis of 2010-2011 revisited; India's okays private RE exploration; China's EV surveillance; Niocorp's Stellantis deal; Prices continue depression.

Rare Earth 16 July 2023 #125

In this post we allocate a lot of space to the old, somewhat myth-laden 2010-2011 rare earth crisis.

Eventually we arrived at a conclusion, which may be disputable, but which we think has a high probability of being correct.

Why it matters: Everybody thinks back then something happened that possibly has not happened, which may lead to misjudgement of the current situation.

Human beings are born with different capacities. If they are free, they are not equal. And if they are equal, they are not free.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, 1918-2008

While U.S. Treasury Secretary Yellen visited Beijing, China’s president visited the PLA’s most important Eastern Command in Jiangsu Province.

Goldman says West needs over $25 billion investments in rare earths to match China

Goldman Sachs on Thursday said the West may need more than $25 billion in investments to match China's supply of rare earths, as export curbs by Beijing on minor metals fuel fears that rare earths could be next.

Mining more than 70% of the world's NdPr and accounting for over 90% of the downstream metal and magnet segment, China increased its output to around 50,000 tons this year from about 34,000 tons in 2021, the bank said.

Replicating China's 50,000 tons per annum output could cost the West anywhere between $15 billion and $30 billion, Goldman estimated.

US-bankers only know how to deal with problems, if these can be solved by input of capital and labour.

In terms of rare earths Goldman’s spreadsheet-acrobats appear to be thinking in the rather confined space between the wallpaper and the wall.

What exactly would the West do with Goldman’s 50,000 t of NdPr? At this time the West does not even have a home for additional 5,000 t NdPr.

Apparently these guys & gals don’t read The Rare Earth Observer….

We have been digging deep on the China intranet behind the Great Firewall of China into recent history, on our quest for some truth.

Much Ado About Gallium, Germanium… and Rare Earth Elements?

In light of the news this week, rare earths have also re-entered the limelight with many of our clients, and others in the media, questioning if they could be next on China’s list of restricted exports – after all, the nation famously but temporarily halted rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 at the climax of a territorial dispute.

To that question, we do believe the potential for China limiting rare earth or magnet exports is now higher than it was before it pulled the germanium and gallium card, albeit the potential is still low and unlikely in our view.

The export limitations on gallium and germanium that China has currently tabled are retaliatory, in response to the U.S. Chips Act and other policies, and are directly targeted at those industries and players that it feels attacked by.

In essence, the U.S. and its allies are telling China “‘no chips or chip making equipment for you” and China is responding by limiting the flow of potatoes.

On the former we are not sure, on the latter Adamas are spot-on right.

We say

The territorial dispute acrimony in 2010 with Japan and the halt of rare earth exports in 2011, including to Japan, may not have been directly related.

General background

From the 1980s China exported whatever it could, incl. rare earth, in order to generate foreign exchange for buying machinery and equipment from abroad. A US-dollar was everything, a RMB was nothing. RMB-based cost did not matter, as long as the result produced US-dollars.

Related, the rare earth policies had been comparatively permissive.

Following China's entry into the WTO in 2001, their foreign exchange earnings experienced rapid growth. When China's foreign exchange reserves reached US$1 trillion in 2006, the country started implementing policies to pursue its national interest, including the regulation of rare earth minerals. Around 2010, several countries, not just the usual suspects, began challenging China's anti-free-trade practices at the WTO regarding various raw materials, including rare earth minerals. These practices included export quotas, minimum export prices, export taxes, and restrictive export licenses.

The run-up to the crisis

Qualification of export companies:

On November 6, 2009, China’s Ministry of Commerce had introduced regulations to limit rare earth trade to:

Exporters with a previous minimum track record of compliant exports of rare earths;

Clean record of no legal or regulatory violations;

Only product from compliant rare earth manufacturers and mines;

Only product that meets China’s national quality standard

ISO 9000 quality management certification;

Largely exempted: 10 foreign rare earth companies in China.

Production quota:

The production quota of 2009 had been 119,500 t for mining and 110,700 t for smelting and separation;

For 2010 the mining quota was set to 89,200 t, a reduction of 25% year on year, while the smelting and separation quota was set at 86,000 t, a reduction of 22% year on year.

Export Quota:

There had been a yearly export quota for rare earths since 1999;

The explanation for this change according to the wind direction. We think the quota was primarily designed to protect state-owned enterprise (SOE) from the - at the time of implementation rather moderate - competition of Chinese private enterprise;

Export quota numbers: You can download the history of China’s rare earth exports from 1992-2011 by private-, state-owned- and foreign invested enterprise and the applicable quota here:

Do note, that the quota was not evenly distributed between the three different types of companies. State-owned enterprises had a much higher share of the quota.

Export tax:

WTO incompatible export taxes have been applicable to rare earths exports since November 2006, implemented from 2007, 5% to 25%, depending on product;

The export taxes were abolished at the end of 2014 and replaced with the China domestic resource tax on rare earths concentrates/carbonates - effective 1 September 2021.

Here you can download the yearly China rare earth export tax rates from 2007-2011:

Administrative action

On May 17, 2010, the “Special Rectification Action Plan for the Development Order of Rare Earth and Other Minerals” was put into force by the Ministry of Land Resources;

On May 18, 2010, "Notice of Special Actions for Mineral Development Order” was published;

From June 2010 to this order was carried out as a “rectification campaign”;

After the campaign the Ministry of Land Resources published a list of compliant mines on October 11, 2010, effectively declaring everyone else being non-compliant.

China also reduced the export quota from 48,000 t for 2009 to just above 30,000 t for 2010, a minus of 37.5%.

Even with all the illegal output of rare earths around, the large reduction of production quota from 2009 to 2010 paired with an unprecedented “rectification campaign” simply had to have an impact.

And it did.

Senkaku crisis preceding rare earth price development

Key rare rare earth products price increases from January 4 to September 1, 2010 - BEFORE the Senkaku Incident:

NdPr +60%

Neodymium oxide +70%

Praseodymium oxide +74%

Terbium oxide +122%

Dysprosium oxide +118%

Senkaku incident price peak

Then the Senkaku Incident happened on on September 7, 2010. A two month diplomatic standoff between Japan and China ensued, at the end of which Japan decided it was not worth it and gave in to most of China’s demands at the beginning of November 2010.

You can see the the price rising strongly from June to September, quite likely the impact of the “rectification campaign”, unrelated to the Senkaku Incident.

Preamble to the developments 2011

On November 15, 2010 China’s Ministry of Finance announced:

Higher export tax rates for rare earth fluorides, lanthanum chloride, lanthanum- and cerium metal;

Increase of export tax rate of neodymium metal from 15% to 25%;

Export quota/quantities to be announced later (again just above 30,000 t for 2011).

On the same day China’s Ministry of Commerce published the names of 22 domestic companies plus 10 foreign companies entitled to apply for rare earth export licenses.

The production quota for 2011 was increased to 93,800 t for mining and 90,400 t for smelting/refining, both roughly up 5% year on year, but still far below the 2009 quota and thus not enough to tame the price development.

There we had it:

Insufficient output, low export quota, increased export duties, limits on qualified exporters, and all that in an environment of already increasing prices.

And this brings us straight to:

The price spike of 2011

Due to the impact of a.m. measures rare earth prices were increasing by 20% per month during Q1 2011.

Then, from March 31, 2011, supercharging the rising rare earth prices, a another massive, all-out 3-months joint rectification operation by

Ministry of Industry and Information Technology,

Ministry of Supervision,

Ministry of Environmental Protection,

State Administration of Taxation,

State Administration for Industry and Commerce, and

State Administration of Work Safety

was launched.

Note that the General Administration of Customs, a ministry level institution directly under the State Council, was not among the authorities called to action - which would have been mandatory for enforcing an export embargo.

During this campaign, apparently ca. 600 illegal rare earth mining sites were raided and closed, 89 rare earth processing companies were suspended for rectification and 10 rare earth smuggling rings were unraveled.

We can’t help noticing, that 89 processing companies mentioned above exceed the indicative total number of 70 “official” rare earth processing companies in China in 2010, as per our data.

To add impetus, the State Council issued the famous "Several Opinions of the State Council on Promoting the Sustainable and Healthy Development of the Rare Earth Industry" on May 19, 2011.

Already strongly rising, rare earth prices went absolutely ballistic from March 2011:

NdPr, neodymium, terbium and dysprosium oxide prices reached historical peaks in July 2011. Praseodymium oxide did not reach a historic peak until March, 2022.

The official export volume of 35,000 t of legal rare earths in 2010 dropped to 15,000 t in 2011.

What about Japan, then?

Rare earth contracts the world over were affected, not only Japan’s.

Then and now, the only really meaningful rare earth market outside China was and is Japan, destination of roughly ⅓ of China’s rare earth exports, and therefore Japanese rare earth buyers were naturally disproportionally hit.

Of course today it is politically convenient for China if the world believes the embargo happened, fearless, tough defenders of Xi Jin Ping Thought. But did they really do it?

2011 official/legal rare earth exports dropping by more than half of 2010 may be viewed as evidence of shuttering export channels. But in such strongly rising markets for whatever products, end users tend to abstain from buying.

What role did illegal production and illegal exports play?

Between 2006 and 2008, China's export statistics indicated up to 30,000 tons per year less than the overseas import statistics for rare earth minerals from China. This suggests that illegal exports accounted for approximately 50% in addition to the legal export quantity. In 2011, illegal exports were even 2.2 times higher than the legal exports of rare earths. However, this was because China's official/legal exports had decreased by half, not because illegal exports had increased.

In other words, it is likely that the level of illegal rare earth exports remained consistent at around 30,000 tons. Although the Ministry of Commerce listed 32 companies with rare earth export licenses, researchers later discovered 55 approved rare earth exporters in China Customs' 2011 database. This raises questions about the accuracy and control of the export licensing system - and about compliance.

What was the point?

The Chinese government has always maintained that its measures were necessary for environmental and resource conservation reasons. They have always denied that any form of embargo happened.

Our take is one word only: Price.

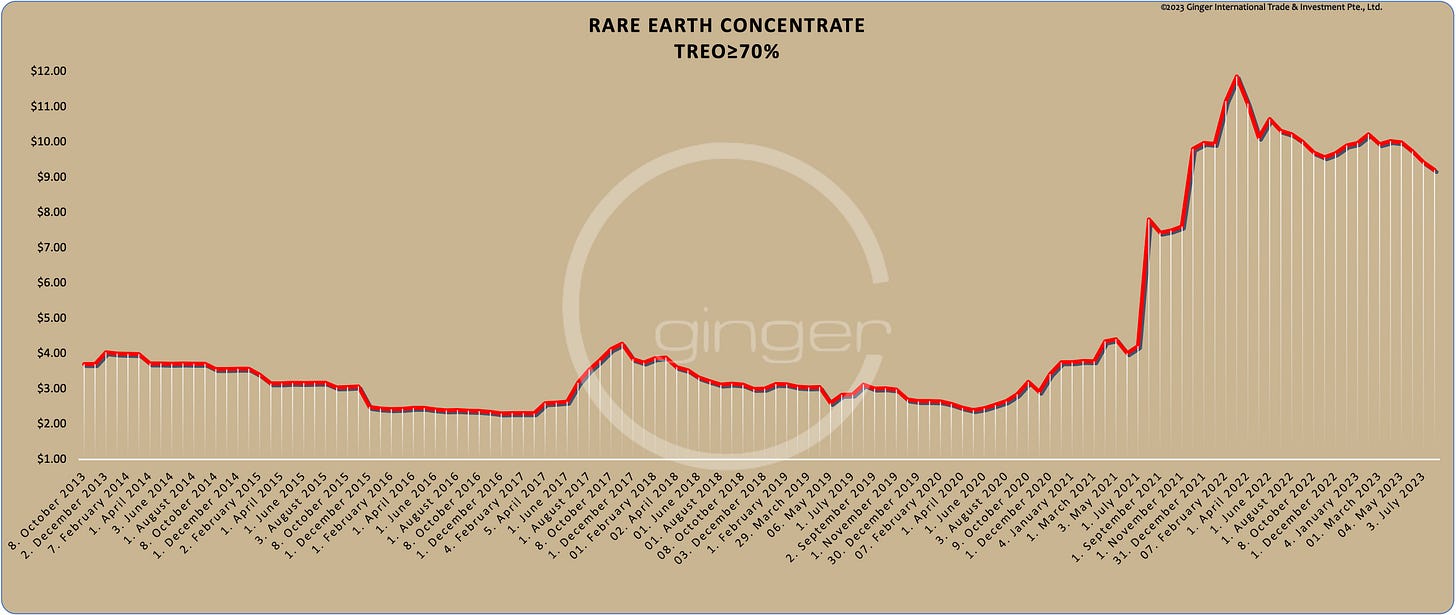

NdPr price net of VAT was less then US$7/kg in late 2005. And mixed rare earth carbonate net of VAT cost US$1.20/kg, falling to below US$1/kg in Q1 2009.

One analyst said, that in the run-up to the crisis (and soon after), mixed rare earth carbonate was sold at ⅓ of its intrinsic value, while neodymium compounds and neodymium metal were sold in average ca. 60% below production cost.

Rare earth carbonate:

Rare earth carbonate reached its lowest point only in 2009, but nonetheless it is credible that it may have been sold below its intrinsic value.

NdPr (75% neodymium content >75%):

If we assume that the average NdPr price of US$15.87/kg during the period of 2006-2008 was indeed 60% below the production cost, it would imply that the production cost should have been around US$40/kg during that time. However, this claim lacks credibility as production costs did not reach that level until August 2021 on significantly increased raw material cost.

It appears that the analyst selectively chose the lowest price points at the beginning of 2006 and at the end of 2008 to support his statement. This approach may have shaped the narrative to fit their argument.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that China's government wanted to assert greater control over the market-price and reduce reliance on foreign entities, particularly Japanese companies. This perspective stems from a belief that any issues or challenges faced by China are often attributed to “hostile foreign forces”, with the exception of natural disasters. This narrative aligns with the image of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) being infallible and always acting in the best interest of China.

The price issue

The core of the rare earth price problem at the time was Baotou Steel and what later became China Northern Rare Earth Group, the world’s largest rare earth company. With a multi-metal resource like the Bayan Obo mine (basically a magnetite, niobium, LIGHT rare earth resource), you can beautifully play around with cost allocation.

Undoubtedly, given the rapid growth in steel consumption, Baotou Steel prioritised iron ore and steelmaking, with rare earths being a bit like a stepchild.

The income generated from the rare earth by-product, regardless of the price, seemed acceptable to them. This alone would not have been problematic if there weren't other dedicated rare earth manufacturers in the market. However, these competitors did exist, and the creation of China Rare Earth Group in 2021 can be seen as a direct response to the excessive market power of China Northern Rare Earth Group.

It became essential to address the issues within Baotou Steel and China Northern. Various reform efforts were made, including mergers, de-mergers, reassignment of subsidiaries, pricing reforms, and accounting changes. However, no matter what reforms were implemented, those in Baotou and Hohot always seemed to find a way around them. To complicate matters further, until a few years ago, top managers held positions in both companies simultaneously, leading to challenging negotiations over raw material prices between literally one and the same persons on both sides of the negotiation table.

As a counter-measure settlements between these two state-owned companies were made subject to shareholder scrutiny and approval, with Baotou Steel and China Northern abstaining from voting to ensure fairness and transparency in the decision-making process. Look at what happened, when this was put into practise:

Same with monazite, suddenly much higher prices for rare earth concentrate were agreed between Baotou Steel and China Northern.

(Yes, we know that Baotou’s concentrate for China Northern is only >50% TREO, but in market price reports these transactions are reflected proportionally. )

This occurrence played a crucial role in triggering the rare earth boom from late 2021 to the first quarter of 2022, as the prices for finished rare earth products followed suit. The Chinese government couldn't help but take notice of this situation, realising that the high rare earth prices were negatively impacting downstream industries and undermining competitiveness in sectors such as permanent magnets and electric vehicles. Consequently, starting from January 2022, the government (MIIT) intervened once again to bring down the prices of finished rare earth products, aiming to restore balance and promote the growth of these vital industries.

How this relates to 2010-2011

The events that unfolded in 2010-2011, in our perspective, bore remarkable similarities. The government implemented heavy-handed measures and/or reforms, leading to a loss of control over the situation. From our point of view, it is important to note that the administrative mess created by China's bureaucrats at that time was unrelated to the Senkaku Incident, both prior to and following its occurrence. The two incidents should be viewed as separate and distinct from each other.

But how about the illegal production?

How illegal producers and exporters could profitably exist: Illegally mined resources reportedly had a rare earth recovery rate of mere 5%, while the recovery rate of legal production was above of 70% (vs. ministerial targets >90%).

For the heavy rare earth resources they paid a pittance, and as late as 2013 illegal rare earth producers stole rare earth concentrates from stockpiles of licensed producers at night.

This lead to the fencing, guarding and nighttime illumination of major rare earth mines and producers.

The fall

On July 21, 2011 rare earth prices began falling, and continued their decline for years.

Why the fall?

天高皇帝远

Heaven is high and the emperor is far away

Proverb when the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty ruled China. First Yuan emperor was Kublai Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan

At the time, central government decrees had the inherent property of literally evaporating at Beijing city limits. Implementation and enforcement of central government decrees at provincial and local level was considered being entirely optional.

Most career-relevant for local officials had been the increase of local GDP, nothing else really mattered. Anti-rare-earth was anti-GDP growth in the relevant areas of China.

Considering this background it is no surprise that after the 2011 rare earth rectification campaign had been over, it was seen as a one-off, same as the campaign the year before. Everyone went back to work and continued doing exactly what they had done before, which brought back rare earth availability and even oversupply, with the predictable impact on the sky-high prices.

Enforcement was simply unsustainable on the rotten base at that time. “Change through trade” had worked very well.

The aftermath

After the WTO case against China’s export restrictions in rare earth had been won, at the end of 2014 almost all restrictive measures and export duties on rare earths were abolished, sending the prices down even further.

But also in 2014 , the Ministry of Information and Information Technology issued the "Guidelines for the Formation of Large and Rare Enterprise Groups", 6 state-owned rare earth groups began to integrate the nation’s rare mines and smelting and separation enterprises.

Today there are 4 rare earth groups left, but the consolidation is not yet complete.

What remains of the trade-impacting rules are the withholding of VAT-refund upon export for rare earths since 2005 and the prohibition on rare earths export processing of imported raw materials since 2006.

MP Materials keep telling their investors, that MP ship their bastnaesite to China “for processing”. This implies to investors, that finished rare earth products find their way back to MP Materials. Quite obviously this has been illegal for 17 years and it is not happening.

So, will they or will they not?

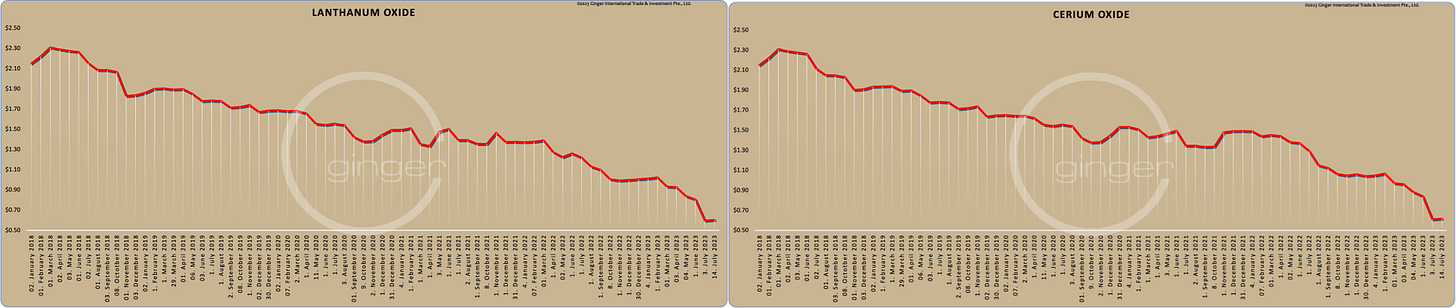

Please remember, 70% of China’s exports are uneconomic lanthanum and cerium. Owing to the rare earth inherent imbalance these are overproduced, in order to produce enough magnet materials:

Prices of lanthanum and cerium oxides have declined from ~US$2/ kg in 2017 to US$0.60/kg in 2023.

China absolutely needs to export as much as possible of both, La and Ce. Even with exports in full swing, prices for both products continuously decline on hopeless oversupply (that is, why so much research and effort in China goes into finding new, large volume applications of both, La and Ce. Mission-critical for rare earths in general).

A selective export embargo of individual rare earth products by HS-code and selective destinations is thinkable.

Rare earth export restrictions will only beg for reciprocity. So, what happens, if affected countries say that under such circumstances they won’t take La and Ce anymore, ban La/Ce imports from China and instead start buying from IREL, Lynas, MP Materials and later from Iluka? Bump!

In embargo-wise much more meaningful rare earth permanent magnets China built and continues building so much additional capacity, particularly for EV high strength NdFeB, that this industry absolutely needs to export - and Beijing wants these exports, too, to keep western magnet developments in check.

China is and remains a nation built on exports. No Xi Jin Ping Thought and no mantra of the naïve “dual circulation” concept is going to change that.

Politics trump economics, true, but China is still ailing from the impact of Xi Jin Ping’s trademark “Zero-COVID” policy. China’s economy needs no further aggravation of the situation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Rare Earth Observer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.